Three Ideas That Are Shaping My Acquisition Path

Choosing what to build and what to avoid.

Hello and welcome back to Buyout Diary.

In the last newsletter, I pulled the curtain back a little on what the past weeks have looked like from the inside. I wrote about the early days of ETA Amsterdam, about the RSM ETA Conference in Rotterdam, and about what it feels like to move through this space not just as a student of entrepreneurship through acquisition, but as someone actively building a path into ownership. It was a more personal broadcast than usual, and the replies I received showed me that many of you are quietly standing in a similar place: still in motion in your own careers, still preparing, still learning, but already committed to this idea of buying and stewarding a small business.

Since then, nothing explosive has happened on the outside. There was no big announcement, no signed deal, no dramatic career pivot. But internally, some things have become clearer. December is a good month for that. The world is still noisy, but there is slightly more space to think. And in that space, three ideas have started to crystallise in a way that I can no longer ignore. They are not brand-new ideas, but they have moved from the background into the foreground. They are shaping how I look at potential acquisitions, which conversations I prioritise, and where I want to position myself in this ecosystem.

Today’s newsletter is about those three ideas. One comes from the conversations and events of the last weeks, especially Rotterdam. One comes from a book I have on my nightstand. And one comes from a question that keeps returning whenever I think seriously about AI and the future of work. Together, they are quietly defining what kind of owner I want to be and what kind of business I am actually willing to live with for a long time.

Where I Really Am Right Now

After Rotterdam, a few people asked me how I see my own path now. Am I going to launch a traditional search fund, raise a committed pool of capital, and go all in on that model. Am I looking for a job in private equity or at a HoldCo. Am I going to stay in my current role and just “think about” acquisitions on the side for another few years. There is a natural curiosity about which box someone fits into, because it makes it easier to categorise them.

The honest answer is that I do not fit neatly into any of the standard boxes, and I do not want to. I have explored the search fund model enough to know that it is not my path. Not because there is something wrong with it in general, but because it imposes a rhythm and a set of expectations that do not align with my temperament. A pre-funded search fund brings structure, mentorship, and a salary, which is attractive for many. But it also brings an obligation to exit, a layer of investor oversight, and a governance framework where your role as CEO is, at least in theory, replaceable if things do not go as planned. For someone who wants to be the long-term steward of a business, not just the operator for a defined investment period, that can feel like wearing the wrong suit.

What became clearer to me in the last weeks is that I want to build my path around ownership first and structure second. I want to own a small number of essential, real-world businesses under Wakonda Ventures, and I want to hold them for a very long time. I want capital partners who are aligned with that kind of horizon, rather than with a fixed exit date. I want governance that helps us think better, not governance that exists primarily to enforce a fund’s constraints. This does not mean ignoring discipline or ignoring investors. It means being honest about the kind of tension I can live with for the next decade.

So when I say I am in a “quiet” phase, it does not mean nothing is happening. It means I am making decisions that will be hard to undo later. I am narrowing my focus to certain types of businesses and letting other ideas die, including some that sounded clever but do not fit who I am. I am learning to be comfortable with the fact that this stage does not always produce screenshots and updates. It produces something more subtle: a clearer filter.

This filter has been influenced not only by what I see around me in the ETA community, but also by what I read when the day is done.

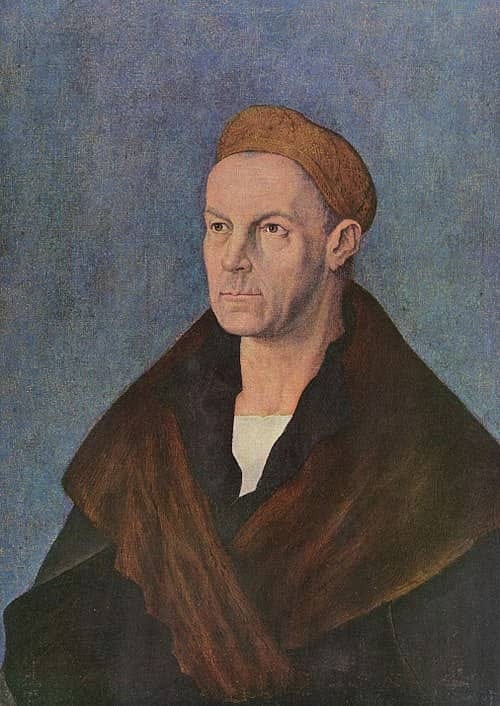

What I Am Reading: Jakob Fugger And The Old Roots Of ETA

In the evenings, I have been reading The Richest Man Who Ever Lived by Greg Steinmetz, the biography of Jakob Fugger. Most people today have never heard of him, but for a time he was arguably the most powerful businessman in Europe. He financed emperors, shaped politics, and controlled some of the most important mining and trading operations in his era. What makes him interesting to me is not the absolute level of his wealth, but the way he thought about business and power.

Fugger was not a startup founder in the way we use the word now. He did not spend his life dreaming up new products and building teams from zero. His genius lay in acquiring and controlling assets that already produced cash flow, and then using capital, information, and relationships to expand and defend those positions. He would finance a mine, secure the rights to the output, and ensure that his family was at the centre of the value chain. He understood that the person who owns the cash-flowing asset has more influence than the person who simply works in or around it.

What really stands out in Fugger’s story is his relationship with Maximilian I, the future Holy Roman Emperor. Maximilian was ambitious, charismatic and endlessly short on cash. He wanted influence. He wanted expansion. He wanted the Habsburgs not just to survive history, but to shape it. But wanting power without liquidity is like wanting a business to scale without working capital: the engine doesn’t turn. So Maximilian turned to Fugger. And Fugger didn’t just lend him money, he negotiated something far more enduring. In exchange for financing military campaigns and political manoeuvres, Fugger secured monopoly access to the richest silver mines of Tyrol, placing himself at the centre of Europe’s most vital economic artery. Silver was not just a commodity. It was coinage. It was government. It was leverage.

To me, that is the ETA mindset in its original form. Fugger didn’t chase growth stories or gamble on unproven markets. He tied himself to essential economic infrastructure; the kind of value that does not disappear when trends shift. And he understood the human side of deal-making: who needs whom, who makes decisions under pressure, who can be aligned through incentives, and where long-term control really sits. Every acquirer today faces a similar crossroads. Do you buy something that looks exciting in a pitch and in five years may not exist? Or do you secure the kind of business people will still rely on decades from now, and then invest yourself into its future? Fugger chose the latter. And reading his story reminds me that the difference between noise and power is often just the patience to own what matters longer than others are willing to.

What strikes me when I read about him is how similar some of his decisions feel to the way a modern HoldCo or ETA entrepreneur might think, even though he lived centuries ago. He paid attention to industries other people underestimated. He cared about who owed him money, and what that meant politically. He understood that if you extend capital to the right counterparties at the right moments, you can quietly shape outcomes far beyond the numbers on a ledger.

There is a passage in the book that describes how he approached risk. It does not romanticise him; he made bets that were uncomfortable and sometimes deeply controversial. But there is a thread that runs through his story: he was willing to tie his fate to assets and relationships he understood, and he was patient enough to let those choices compound. He did not need to be visible to be powerful. He needed to control the things that mattered.

Reading about Fugger reminds me that the logic behind ETA is not new. The idea of buying what already works, rather than always starting from nothing, is as old as trade itself. The difference today is that we have given it a name, we have wrapped it into a community and a playbook, and we are trying to adapt it to a world where technology can both amplify and destroy value very quickly.

When I put the book down, I do not think “I want to be Jakob Fugger”. That is not the point. I think about what it means to choose ownership over activity. I think about what it means to bind yourself to a small number of businesses and to see them as something more than “assets”. And I think about the responsibility that comes with that, especially when the world is changing as quickly as it is now.

That brings me to the third idea that has been on my mind: the question of which business models actually deserve to be acquired in a world where AI is not going away.

Thinking Ahead: Which Business Models Are Still Worth Buying

It is very easy, especially in ETA circles, to talk about valuations, multiples, and deal structures as if we are all operating in a steady environment. We look at trailing EBITDA, at recurring revenue, at customer concentration, and all of that is important. But there is a deeper question underneath the spreadsheet that we rarely ask out loud: is this business model going to matter in ten or fifteen years, or is it already being slowly eroded by technology, even if this year’s numbers still look healthy.

AI forces that question into the open. Not in a dramatic “robots will take over everything” way, but in a quieter, more uncomfortable way. If a business exists primarily to perform repeatable tasks that can be automated, then owning that business long term is like buying a building on a piece of land you know the sea is quietly eating away. The erosion is slow, but it is constant. Yes, you can still make money in the short run. Yes, someone will still buy those services for a few more years. But is that really what you want to tie your identity and your capital to.

When I look at potential acquisition targets now, I find myself asking a simple but unforgiving question: where does the human still make the real difference here. If the answer is “nowhere, really, the value is speed and low cost”, then I know that AI or some other form of software will eventually do it better. Not tomorrow. But soon enough that owning the business will become a game of defending shrinking margins and cutting costs instead of building something that gets stronger over time.

There are a few categories that feel particularly fragile to me. Businesses that are essentially packaging and reselling generic digital work, for example, without a clear niche or a deep relationship with the client. Agencies that exist mostly to produce content at volume. Back-office operations where the only promise is “we do the repetitive thing for you so you do not have to think about it”. Pure compliance functions that do not move into advice or insight. These are all vulnerable, because their core promise can be replicated and scaled by software that never gets tired.

On the other hand, there are business models where technology actually strengthens the underlying value proposition if it is used intelligently. These are usually the ones where the human is not there to push buttons, but to provide judgement, context and trust. An accountant who simply enters data into a system is at risk. An accountant who acts as a strategic financial partner, who understands the client’s business, who can interpret what the numbers mean and help navigate decisions, becomes more valuable when technology takes some of the manual work away. The same is true in many service businesses: if your real asset is the relationship, the local presence, the trust you have built, then AI becomes a tool, not a threat.

So when I think about what I want to acquire and own under Wakonda Ventures, I am increasingly drawn to businesses that sit in this second and third category. Essential services in the real world, where people will still need someone to show up, to decide, to coordinate, to fix, to advise, to translate complexity into something they can act on. Businesses that may not look glamorous on the outside, but are deeply embedded in how other people live and work. Business models where technology can help streamline operations, improve decision-making, and make life easier for staff and customers, but where it cannot replace the core human contribution.

This is not a neat formula. It is more of a feeling that guides the filter. When I look at a business now, I ask: is this somewhere I would be comfortable living as an owner for ten or twenty years, knowing that the world will change. Would I be proud to be associated with this sector. Does it feel exposed to the wrong kind of disruption. Or could I imagine using technology to make it stronger, calmer, and more robust.

These questions do not produce a perfect answer, but they remove a lot of noise. And that, in itself, is valuable.

One Collaboration I Am Opening Myself Up To

There is one more piece that has emerged from these reflections, and it is a bit more personal.

Over the last months, through the newsletter, ETA Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and many one-to-one conversations, I have noticed that there is a specific kind of support that many people in this space are looking for. They do not just want more tools or more templates. They are not looking for someone to do their operations for them. What they seem to need most, especially in the early stages of a search and in the first year of ownership, is a thinking partner.

Someone who is close enough to understand their specific situation, but not so entangled that they lose perspective. Someone who can read a CIM and notice the things that are not being said. Someone who has spent the last years immersed in questions of governance, delegation, founder transitions and knowledge transfer, and can bring that lens into real deals. Someone who is calm, honest and not trying to impress anyone.

Alongside my own search, I have decided to open myself up to exactly one long-term remote collaboration of that kind. I imagine it as a steady, thoughtful partnership alongside a searcher, a small HoldCo, an independent sponsor, or an ETA investor who values depth more than noise. It would be around ten to fifteen hours per week, fully remote, and focused on the early decision-making side of the journey rather than on operational firefighting.

The scope could include things like early deal screening and first-pass analysis, identifying red flags and decision points, reading CIMs with a critical, owner-oriented lens, doing market and sector research to make sure the target sits in a defensible space, and bringing in governance insights from my dissertation work to think about what happens after the deal closes. In other words, the slow, reflective part of ETA that often gets rushed because everyone is eager to “do” something.

This is not meant to replace a junior analyst or an intern. It is not a way to get cheap labour. It is a collaboration with someone who wants a consistent thought partner as they move from interest to ownership, and who understands that reflection is not a luxury, but a protective layer. Compensation will depend on the scope we define together. It is not a volunteer role, and I want it to feel fair for both sides, especially if it runs over a longer period.

If you are reading this and something about this idea speaks to you, or if you know someone who might appreciate working in this way, feel free to reply to this email or send me a short message on LinkedIn. There is no urgency and no pressure. I am opening only one such collaboration, and if the fit is there on both sides, we will know it when we talk.

👉 Let’s talk!

Closing Reflection

When I look at these three ideas together, they feel connected. Clarifying how I want to own changes how I see history, and that in turn changes how I look at technology and the future. Reading about Jakob Fugger does not give me a playbook, but it reminds me that ownership has always been a serious role, not a side project. Thinking about AI does not make me anxious, it makes me more selective. And being more selective, in turn, makes me more comfortable with moving slowly, because I know I am not just chasing any deal; I am preparing for the right kind of responsibility.

If you are somewhere on a similar path, thinking about buying a small business, or already searching, or still sitting with the idea and wondering if you are “ready”, I hope this gave you a few things to reflect on. Not as advice from someone who has everything figured out, but as a field note from someone who is in the middle of the same transition.

Thank you, as always, for reading.

If something in this letter resonated with you, I would be happy to hear from you.

Warm regards,

Alexander